He quotes economics Professor Robert Frank of Cornell University, who notes that "animals will fight viciously to protect territory that they hold, but they won't fight nearly as hard to extend their territory." Most humans have this same protective instinct, which is why we tend to be more motivated by fear than desire.

Why should business people care? Think about those times you tried to sell an idea, make a proposal or get someone's help and you got a "no." Chances are there is some fear behind the response. Think about the following examples:

- Your boss dumped a bucket of cold water on your last budget request. (He was worried that if his boss called him on the expenditure, he wouldn't be able to defend it, making him look bad.)

- Your boss dumped a bucket of cold water on your last budget request. (He was worried that if his boss called him on the expenditure, he wouldn't be able to defend it, making him look bad.)- Your process improvement idea was rejected by other departments, despite the fact that it would save the company thousands of dollars. (They like their current processes, they created them, and only they understand them. Now you want to take that all away.)

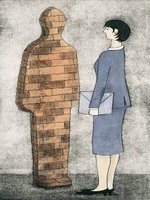

- You hit a brick wall when you asked someone from your IT Department to show you how to fix your own computer problem. (They felt threatened. If they show you how to fix your own problems, you won't need them.)

Granted, not every decision is fear-based. But you can have greater influence over others if you tune into their worries and fears.

Below are some pointers for getting more "yes" responses to your ideas and proposals by finding people's hidden fears - and alleviating them...

Before presenting your idea or proposal:

- Stay objective - No matter how good your idea is or how much time and money it will save, don't assume that just because you're excited about your idea, others will be.

- Play devil's advocate with yourself and someone else - Before presenting your idea, test it. List all of the possible arguments against it...and go beyond the obvious. For example, if you're asking for a raise, think beyond the actual dollars. Even if there is budget for your salary increase, your boss may be afraid that if he gives you the raise and word gets out, others will ask for more money as well. Check yourself by asking an objective third party - preferably someone who knows the person to whom you're presenting the idea - to play devil's advocate with you. That person will likely think of arguments against your idea that you've missed.

- Figure out how to "Tip the Value Scale" - Imagine that inside everyone's head is a little scale - the "Value Scale." Humans use this value scale to make decisions. The scale helps the brain weigh the benefits (gains) they'll receive from saying "yes" to a decision, versus the losses (fears) they'll face if they say "yes". Since the loss/fear side of the Value Scale can be a more powerful motivator than the benefit/gain side, your job as the proposal-presenter is to get inside the other person's head and tip that scale, so that the gain outweighs the fear. You've got to figure out, "What is it going to take to alleviate that person's fear of my proposal?" and "How do I tip the 'value scale', so that in the other person's head, the gains from my proposal outweigh the fears about it?"

- Think about other influencers or decision-makers - A note of caution. Make sure that you're presenting your proposal or idea to the right person. Ask yourself, "Is this person truly the decision maker, or will he/she have to check with others for approval?" If others are likely to influence or be involved with the decision, you must assess each person individually. Everyone has different concerns and fears. Make sure that you've thought through each person's value scale and prepare to address potential fears. For example, when you're asking the person in your IT Department to help you, think about who else might be impacted if he says "yes". Not only may the IT person be threatened by your desire to learn how to fix your own computer problem - but he may also need to ask his manager for an extension on a project deadline because he'll be spending more time with you (it would be quicker for him if he just fixed your problem and went back to his project). In other words, his manager's fear may be that the project work won't get done because the IT person is wasting time teaching you how to fix a problem. To get the IT person to help you, you may need to help him think about how to ask his boss for the project deadline extension.

When presenting your idea or proposal:

- Ask first - Don't start the conversation by launching into an explanation of your idea, or trying to sell the benefits. It's important to get the individual talking, so you can confirm whether your assessment of the person's fears and desires was accurate. For example, if you've anticipated that the IT person may resist your request to teach your team how to do basic troubleshooting, you might ask questions such as: "How much time have you spent fixing this problem over and over again for our department?" "What other projects are you working on, when you're not trouble-shooting for us?" "If you didn't have to fix these recurring problems, what could you be doing with your time?" "If our team were willing to invest the time on our end...how would you feel about teaching us some of the trouble-shooting basics - so you could focus on the more complex, business-critical work?" What's good about these questions is that they're addressing the person's potential underlying worry, that he won't be valued, in a non-threatening way. You're helping him see that by teaching your team some basic trouble-shooting, he'll actually increase his value to the organization by focusing on more complex, business-critical work.

- Don't be cagey - Most people can smell a manipulation job a mile away. It's ok to acknowledge the fact that you have an idea or proposal right up front. You might say, "I've been toying with an idea, but first I'd like to ask you a few questions to see if it's even viable." Then start asking your questions. If the person says, "Can't you just tell me your idea and I'll tell you if I like it or not?" it's all right to say, "I could, but I don't want to waste your time trying to sell you on an idea that won't work. If you give me a minute to ask a few questions, I can probably save both of us some time." Very few people will resist that approach, because most people fear having their time wasted, or having a bad idea pushed on them. In most people (because we're such a busy society), these fears will outweigh their desire to hear your idea quickly or skip the questions.

- Acknowledge and encourage challenges - No matter how much analysis you did in advance, you'll occasionally be caught off guard by a challenge you weren't prepared for as you present your idea. Welcome these challenges! In fact, thank the person for bringing up these issues. Once their concerns are on the table, you have the chance to address them. As long as concerns are unspoken, you'll be in the dark about why your ideas are being rejected.

- Tell a story with your proposal - One of the biggest mistakes people make when presenting ideas or proposals is forgetting to put them in context. In other words, forgetting to tell the story of why your idea's benefit (value) outweighs the cost (fear). If you've done your work in advance by assessing the other person's fears and desires, and asked questions to get the person talking about costs and benefits, you have what you need to tell a strong story. A story sounds something like this, when presenting your idea:

- "Here's the idea..."

- "Here's how it's going to address your needs and here's the assessment I've done."

- "I recognize that there are some issues, such as X and Y. Here's how we can address those issues."

- "What additional questions do you have - or what other information do you need?"

- "How should we move forward on this?" or just recommend a next step.

Keep in mind, it's not about using fear to manipulate others. Rather, it's about working to understand what people worry about (what keeps them up at night)...and figuring out ways to alleviate those worries with your ideas. In other words, you get what you want when you're a problem-solver (aka: fear-remover). The best part is, you're giving the other person what they want - making the problem/fear go away.

Are you a salesperson who wants to learn how to be a problem-solver by uncovering customers' concerns and needs? Click here for more information on TLG's Sales in Action programs.